- Money is any object or record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts in a given socio-economic context or country.[1][2][3] The main functions of money are distinguished as: a medium of exchange; a unit of account; a store of value; and, occasionally in the past, a standard of deferred payment.[4][5] Any kind of object or secure verifiable record that fulfills these functions can be considered money.

Money is historically an emergent market phenomenon establishing a commodity money, but nearly all contemporary money systems are based on fiat money.[4] Fiat money, like any check or note of debt, is without intrinsic use value as a physical commodity. It derives its value by being declared by a government to be legal tender; that is, it must be accepted as a form of payment within the boundaries of the country, for "all debts, public and private"[citation needed]. Such laws in practice cause fiat money to acquire the value of any of the goods and services that it may be traded for within the nation that issues it.

The money supply of a country consists of currency (banknotes and coins) and bank money

(the balance held in checking accounts and savings accounts). Bank

money, which consists only of records (mostly computerized in modern

banking), forms by far the largest part of the money supply in developed nations.[6][7][8]

The use of barter-like methods may date back to at least 100,000 years ago, though there is no evidence of a society or economy that relied primarily on barter.[9] Instead, non-monetary societies operated largely along the principles of gift economics and debt.[10][11] When barter did in fact occur, it was usually between either complete strangers or potential enemies.[12]

The use of barter-like methods may date back to at least 100,000 years ago, though there is no evidence of a society or economy that relied primarily on barter.[9] Instead, non-monetary societies operated largely along the principles of gift economics and debt.[10][11] When barter did in fact occur, it was usually between either complete strangers or potential enemies.[12]

Many cultures around

the world eventually developed the use of commodity money. The shekel

was originally a unit of weight, and referred to a specific weight of

barley, which was used as currency.[13] The first usage of the term came

from Mesopotamia circa 3000 BC. Societies in the Americas, Asia, Africa

and Australia used shell money – often, the shells of the money cowry (Cypraea moneta L. or C. annulus L.).

According to Herodotus, the Lydians were the first people to introduce

the use of gold and silver coins.[14] It is thought by modern scholars

that these first stamped coins were minted around 650–600 BC.[15]

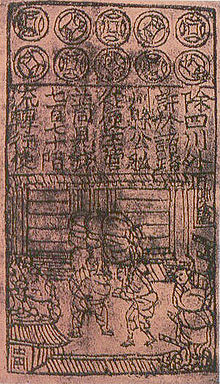

Song Dynasty Jiaozi, the world's earliest paper money

The system of commodity money eventually evolved into a system of representative money.[citation needed]

This occurred because gold and silver merchants or banks would issue

receipts to their depositors – redeemable for the commodity money deposited. Eventually, these receipts became generally accepted as a means of payment and were used as money. Paper money

or banknotes were first used in China during the Song Dynasty. These

banknotes, known as "jiaozi", evolved from promissory notes that had

been used since the 7th century. However, they did not displace

commodity money, and were used alongside coins. In the 13th century,

paper money

became known in Europe through the accounts of travelers, such as

Marco Polo and William of Rubruck.[16] Marco Polo's account of paper money during the Yuan Dynasty is the subject of a chapter of his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, titled "How the Great Kaan Causeth the Bark of Trees, Made Into Something Like Paper, to Pass for money

All Over his Country."[17] Banknotes were first issued in Europe by

Stockholms Banco in 1661, and were again also used alongside coins. The

gold standard, a monetary system where the medium of exchange are paper

notes that are convertible into pre-set, fixed quantities of gold,

replaced the use of gold coins as currency in the 17th-19th centuries

in Europe. These gold standard notes were made legal tender, and

redemption into gold coins was discouraged. By the beginning of the

20th century almost all countries had adopted the gold standard,

backing their legal tender notes with fixed amounts of gold.

After

World War II, at the Bretton Woods Conference, most countries adopted

fiat currencies that were fixed to the US dollar. The US dollar was in

turn fixed to gold. In 1971 the US government suspended the

convertibility of the US dollar to gold. After this many countries

de-pegged their currencies from the US dollar, and most of the world's

currencies became unbacked by anything except the governments' fiat of

legal tender and the ability to convert the money into goods via payment.

Etymology

The word "money" is believed to originate from a

temple of Hera, located on Capitoline, one of Rome's seven hills. In the

ancient world Hera was often associated with money. The temple of Juno

Moneta at Rome was the place where the mint of Ancient Rome was

located.[18] The name "Juno" may derive from the Etruscan goddess Uni

(which means "the one", "unique", "unit", "union", "united") and

"Moneta" either from the Latin word "monere" (remind, warn, or instruct)

or the Greek word "moneres" (alone, unique).

In the Western world, a prevalent term for coin-money has been specie, stemming from Latin in specie, meaning 'in kind'.[19]

FunctionsEconomics

Economies by country

Economies by countryGeneral classifications

- Microeconomics

- Macroeconomics

- History of economic thought

- Methodology

- Heterodox approaches

- Mathematical

- Econometrics

- Experimental

- National accounting

- Behavioral

- Cultural

- Evolutionary

- Growth

- Development

- History

- International

- Economic systems

- Monetary and Financial economics

- Public and Welfare economics

- Health

- Education

- Welfare

- Population

- Labour

- Personnel

- Managerial

- Computational

- Business

- Information

- Game theory

- Industrial organization

- Law

- Agricultural

- Natural resource

- Environmental

- Ecological

- Urban

- Rural

- Regional

- Geography

- Economists

- Journals

- Publications

- Categories

- Index

- Outline

Business and economics portal

Business and economics portal

- v

- t

- e

In the past, money

was generally considered to have the following four main functions,

which are summed up in a rhyme found in older economics textbooks:

"Money is a matter of functions four, a medium, a measure, a standard, a

store." That is, money

functions as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, a standard of

deferred payment, and a store of value.[5] However, modern textbooks now

list only three functions, that of medium of exchange, unit of account,

and store of value, not considering a standard of deferred payment as a

distinguished function, but rather subsuming it in the

others.[4][20][21]

There have been many

historical disputes regarding the combination of money's functions,

some arguing that they need more separation and that a single unit is

insufficient to deal with them all. One of these arguments is that the

role of money

as a medium of exchange is in conflict with its role as a store of

value: its role as a store of value requires holding it without

spending, whereas its role as a medium of exchange requires it to

circulate.[5] Others argue that storing of value is just deferral of

the exchange, but does not diminish the fact that money

is a medium of exchange that can be transported both across space and

time.[22] The term 'financial capital' is a more general and inclusive

term for all liquid instruments, whether or not they are a uniformly

recognized tender.

Medium of exchange

Main article: Medium of exchange

When money is used to intermediate the exchange of goods and services, it is performing a function as a medium of exchange. It thereby avoids the inefficiencies of a barter system, such as the 'double coincidence of wants' problem.

Unit of account

Main article: Unit of account

A unit of account

is a standard numerical unit of measurement of the market value of

goods, services, and other transactions. Also known as a "measure" or

"standard" of relative worth and deferred payment, a unit of account is

a necessary prerequisite for the formulation of commercial agreements

that involve debt. To function as a 'unit of account', whatever is

being used as money must be:

- Divisible into smaller units without loss of value; precious metals can be coined from bars, or melted down into bars again.

- Fungible: that is, one unit or piece must be perceived as equivalent to any other, which is why diamonds, works of art or real estate are not suitable as money.

- A specific weight, or measure, or size to be verifiably countable. For instance, coins are often milled with a reeded edge, so that any removal of material from the coin (lowering its commodity value) will be easy to detect.

Main article: Store of value

To act as a store of value, a money

must be able to be reliably saved, stored, and retrieved – and be

predictably usable as a medium of exchange when it is retrieved. The

value of the money

must also remain stable over time. Some have argued that inflation,

by reducing the value of money, diminishes the ability of the money to function as a store of value.[4]

Standard of deferred payment

Main article: Standard of deferred payment

While standard of deferred payment

is distinguished by some texts,[5] particularly older ones, other texts

subsume this under other functions.[4][20][21] A "standard of deferred

payment" is an accepted way to settle a debt – a unit in which debts are

denominated, and the status of money

as legal tender, in those jurisdictions which have this concept,

states that it may function for the discharge of debts. When debts are

denominated in money, the real value of debts may change due to

inflation and deflation, and for sovereign and international debts via

debasement and devaluation.

Measure of value

Money acts as a standard measure and common

denomination of trade. It is thus a basis for quoting and bargaining of

prices. It is necessary for developing efficient accounting systems.

But its most important usage is as a method for comparing the values of

dissimilar objects.

money supply

Main article: money supply

In economics, money is a broad term that refers to any financial instrument that can fulfill the functions of money (detailed above). These financial instruments together are collectively referred to as the money supply of an economy. In other words, the money

supply is the amount of financial instruments within a specific

economy available for purchasing goods or services. Since the money

supply consists of various financial instruments (usually currency,

demand deposits and various other types of deposits), the amount of money in an economy is measured by adding together these financial instruments creating a monetary aggregate.

Modern monetary theory distinguishes among different ways to measure the money

supply, reflected in different types of monetary aggregates, using a

categorization system that focuses on the liquidity of the financial

instrument used as money. The most commonly used monetary aggregates

(or types of money) are conventionally designated M1, M2 and M3. These

are successively larger aggregate categories: M1 is currency (coins and

bills) plus demand deposits (such as checking accounts); M2 is M1 plus

savings accounts and time deposits under $100,000; and M3 is M2 plus

larger time deposits and similar institutional accounts. M1 includes

only the most liquid financial instruments, and M3 relatively illiquid

instruments.

Another measure of money, M0, is

also used; unlike the other measures, it does not represent actual

purchasing power by firms and households in the economy. M0 is base

money, or the amount of money

actually issued by the central bank of a country. It is measured as

currency plus deposits of banks and other institutions at the central

bank. M0 is also the only money that can satisfy the reserve requirements of commercial banks.

Market liquidity

Main article: Market liquidity

Market liquidity describes how easily an item can be traded for another item, or into the common currency within an economy. money is the most liquid asset because it is universally recognised and accepted as the common currency. In this way, money gives consumers the freedom to trade goods and services easily without having to barter.

Liquid

financial instruments are easily tradable and have low transaction

costs. There should be no (or minimal) spread between the prices to buy

and sell the instrument being used as money.

Types of money

Currently, most modern monetary systems are based on fiat money. However, for most of history, almost all money was commodity money, such as gold and silver coins. As economies developed, commodity money

was eventually replaced by representative money, such as the gold

standard, as traders found the physical transportation of gold and

silver burdensome. Fiat currencies gradually took over in the last

hundred years, especially since the breakup of the Bretton Woods system

in the early 1970s.

Commodity money

Main article: Commodity money

A 1914 British Gold sovereign

Many items have been used as commodity money

such as naturally scarce precious metals, conch shells, barley, beads

etc., as well as many other things that are thought of as having value.

Commodity money value comes from the commodity out of which it is made. The commodity itself constitutes the money, and the money

is the commodity.[23] Examples of commodities that have been used as

mediums of exchange include gold, silver, copper, rice, salt,

peppercorns, large stones, decorated belts, shells, alcohol,

cigarettes, cannabis, candy, etc. These items were sometimes used in a

metric of perceived value in conjunction to one another, in various

commodity valuation or Price System economies. Use of commodity money is similar to barter, but a commodity money

provides a simple and automatic unit of account for the commodity

which is being used as money. Although some gold coins such as the

Krugerrand are considered legal tender, there is no record of their

face value on either side of the coin. The rationale for this is that

emphasis is laid on their direct link to the prevailing value of their

fine gold content.[24] American Eagles are imprinted with their gold

content and legal tender face value.[25]

Representative money

Main article: Representative money

In 1875, the British economist William Stanley Jevons described the money used at the time as "representative money". Representative money is money that consists of token coins, paper money

or other physical tokens such as certificates, that can be reliably

exchanged for a fixed quantity of a commodity such as gold or silver.

The value of representative money stands in direct and fixed relation to the commodity that backs it, while not itself being composed of that commodity.[26]

Fiat money

Main article: Fiat money

Fiat money or fiat currency is money

whose value is not derived from any intrinsic value or guarantee that

it can be converted into a valuable commodity (such as gold). Instead,

it has value only by government order (fiat). Usually, the government

declares the fiat currency (typically notes and coins from a central

bank, such as the Federal Reserve System in the U.S.) to be legal

tender, making it unlawful to not accept the fiat currency as a means of

repayment for all debts, public and private.[27][28]

Some

bullion coins such as the Australian Gold Nugget and American Eagle are

legal tender, however, they trade based on the market price of the

metal content as a commodity, rather than their legal tender face value

(which is usually only a small fraction of their bullion value).[25][29]

Fiat

money, if physically represented in the form of currency (paper or

coins) can be accidentally damaged or destroyed. However, fiat money has an advantage over representative or commodity money, in that the same laws that created the money

can also define rules for its replacement in case of damage or

destruction. For example, the U.S. government will replace mutilated

Federal Reserve notes (U.S. fiat money) if at least half of the

physical note can be reconstructed, or if it can be otherwise proven to

have been destroyed.[30] By contrast, commodity money which has been lost or destroyed cannot be recovered.

Coinage

Main article: Coin

These

factors led to the shift of the store of value being the metal itself:

at first silver, then both silver and gold, at one point there was

bronze as well. Now we have copper coins and other non-precious metals

as coins. Metals were mined, weighed, and stamped into coins. This was

to assure the individual taking the coin that he was getting a certain

known weight of precious metal. Coins could be counterfeited, but they

also created a new unit of account, which helped lead to banking.

Archimedes' principle provided the next link: coins could now be easily

tested for their fine weight of metal, and thus the value of a coin

could be determined, even if it had been shaved, debased or otherwise

tampered with (see Numismatics).

In most major

economies using coinage, copper, silver and gold formed three tiers of

coins. Gold coins were used for large purchases, payment of the

military and backing of state activities. Silver coins were used for

midsized transactions, and as a unit of account for taxes, dues,

contracts and fealty, while copper coins represented the coinage of

common transaction. This system had been used in ancient India since the

time of the Mahajanapadas. In Europe, this system worked through the

medieval period because there was virtually no new gold, silver or

copper introduced through mining or conquest.[citation needed] Thus the overall ratios of the three coinages remained roughly equivalent.

Paper money

Main article: Banknote

In

premodern China, the need for credit and for circulating a medium that

was less of a burden than exchanging thousands of copper coins led to

the introduction of paper money, commonly known today as banknotes. This

economic phenomenon was a slow and gradual process that took place from

the late Tang Dynasty (618–907) into the Song Dynasty (960–1279). It

began as a means for merchants to exchange heavy coinage for receipts of

deposit issued as promissory notes from shops of wholesalers, notes

that were valid for temporary use in a small regional territory. In the

10th century, the Song Dynasty government began circulating these notes

amongst the traders in their monopolized salt industry. The Song

government granted several shops the sole right to issue banknotes, and

in the early 12th century the government finally took over these shops

to produce state-issued currency. Yet the banknotes issued were still

regionally valid and temporary; it was not until the mid 13th century

that a standard and uniform government issue of paper money

was made into an acceptable nationwide currency. The already

widespread methods of woodblock printing and then Pi Sheng's movable

type printing by the 11th century was the impetus for the massive

production of paper money in premodern China.

Song Dynasty Jiaozi, the world's earliest paper money

At around the same time in the medieval

Islamic world, a vigorous monetary economy was created during the

7th–12th centuries on the basis of the expanding levels of circulation

of a stable high-value currency (the dinar). Innovations introduced by

Muslim economists, traders and merchants include the earliest uses of

credit,[31] cheques, promissory notes,[32] savings accounts,

transactional accounts, loaning, trusts, exchange rates, the transfer of

credit and debt,[33] and banking institutions for loans and

deposits.[33]

In Europe, paper money

was first introduced in Sweden in 1661. Sweden was rich in copper,

thus, because of copper's low value, extraordinarily big coins (often

weighing several kilograms) had to be made.

The

advantages of paper currency were numerous: it reduced transport of

gold and silver, and thus lowered the risks; it made loaning gold or

silver at interest easier, since the specie (gold or silver) never left

the possession of the lender until someone else redeemed the note; and

it allowed for a division of currency into credit and specie backed

forms. It enabled the sale of stock in joint stock companies, and the

redemption of those shares in paper.

However,

these advantages held within them disadvantages. First, since a note

has no intrinsic value, there was nothing to stop issuing authorities

from printing more of it than they had specie to back it with. Second,

because it increased the money supply, it increased inflationary pressures, a fact observed by David Hume in the 18th century. The result is that paper money

would often lead to an inflationary bubble, which could collapse if

people began demanding hard money, causing the demand for paper notes

to fall to zero. The printing of paper money

was also associated with wars, and financing of wars, and therefore

regarded as part of maintaining a standing army. For these reasons,

paper currency was held in suspicion and hostility in Europe and

America. It was also addictive, since the speculative profits of trade

and capital creation were quite large. Major nations established mints

to print money and mint coins, and branches of their treasury to collect taxes and hold gold and silver stock.

At

this time both silver and gold were considered legal tender, and

accepted by governments for taxes. However, the instability in the ratio

between the two grew over the course of the 19th century, with the

increase both in supply of these metals, particularly silver, and of

trade. This is called bimetallism and the attempt to create a bimetallic

standard where both gold and silver backed currency remained in

circulation occupied the efforts of inflationists. Governments at this

point could use currency as an instrument of policy, printing paper

currency such as the United States Greenback, to pay for military

expenditures. They could also set the terms at which they would redeem

notes for specie, by limiting the amount of purchase, or the minimum

amount that could be redeemed

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق